I’m a lifelong Jersey boy, living just a few miles from the town I grew up in in South Jersey. And while some things about the Garden State haven’t changed since I was a boy — we still have the best diners, the best beaches, and the best hoagies — one major change is abundantly clear. It’s a lot more crowded now.

In 1970, New Jersey’s population was a little more than 7 million. Today, it tops 9 million. In the past few decades, we’ve added more folks than live in the city of Philadelphia. Don’t believe me? Check out the traffic here in Jersey on a weekday afternoon.

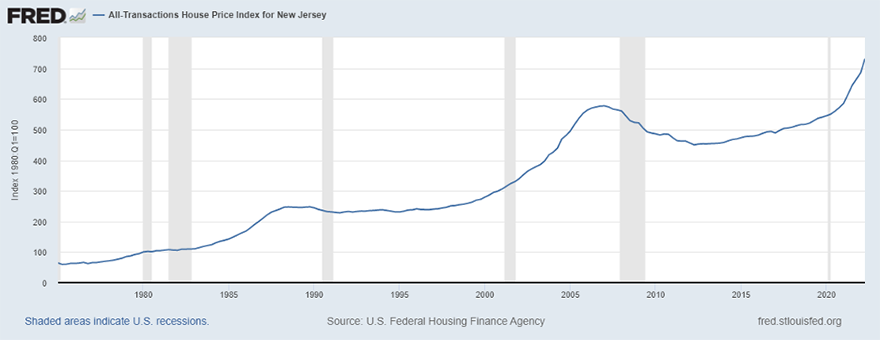

As New Jersey’s population has ballooned, so has the state’s housing stock. For a population of 9.2 million, New Jersey currently has 3.7 million housing units, compared with around 2.4 million in 1970. Yet an odd thing has happened as the supply of housing units has grown along with New Jersey’s population. The cost of housing has soared:

Part of this run-up in prices is simply a result of New Jersey’s high-median incomes and proximity to high-wage work. There is a strong correlation between incomes and home prices.

But other factors are less salutary. Short-term rentals have gobbled up a significant portion of the housing supply, particularly at the Shore, for instance. Airbnb recently announced that Ocean City, New Jersey, was its most booked American destination. (Did I mention that we had the best beaches?)

There is also evidence that the composition of New Jersey’s housing stock could be driving price growth. Although the state has made strides in recent years in building multiunit housing, the majority of homes here are single-family, detached houses, which carry higher costs than apartments and townhouses. Out of all 50 states, New Jersey now has the highest percentage of people ages 18 to 34 living with their parents — 45.4 percent, or nearly half, are still at home. That suggests the state desperately needs to build more affordable homes, which tend to be apartments or townhouses. These would also better match our changing population composition, as Americans now tend to stay single longer and have fewer children than before.

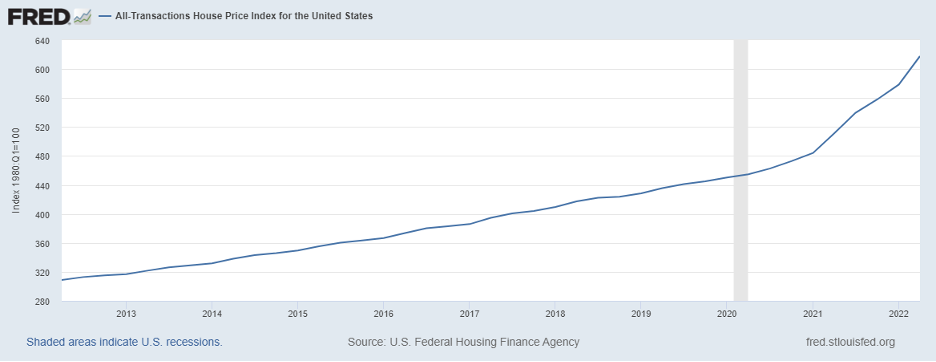

Of course, rising home prices are a nationwide trend and one that predates the COVID-19 pandemic:

Since the Great Recession, the United States has not built enough housing to keep price growth relatively modest. By most estimates, we are now several million homes short of where we need to be.

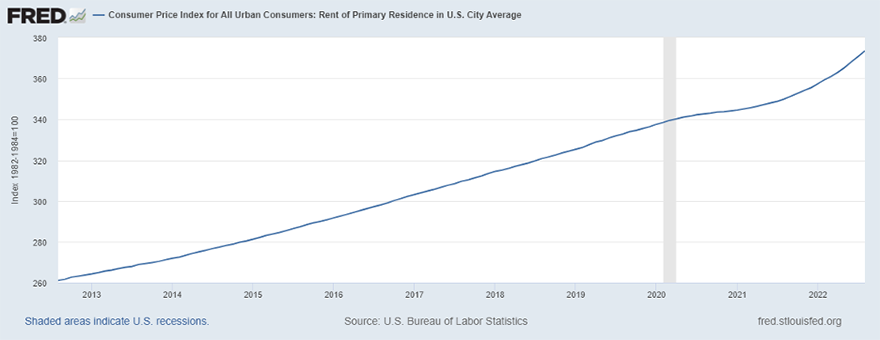

In fact, shelter inflation, as it is known, is a major driver of the far-too-high inflation plaguing our country. Housing represents about a third of the value of the baskets of goods that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) examines when preparing the Consumer Price Index. For renters, shelter inflation measures both rent and utility payments. For homeowners, the BLS calculates what it would cost to rent a similar house. Inflation in other sectors of the economy are also drivers of inflation; if the cost of commodities like lumber rises, so does the cost of building a home. It’s a feedback loop.

Of course, inflation is far too high across most goods and services in our economy. But I find shelter inflation, along with food inflation, particularly alarming. Food and shelter are quite literally essential; it’s no wonder they are considered the most basic category on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. We must do everything we can to get shelter inflation under control.

Monetary policy has a role to play here, and the Federal Reserve is working to stabilize inflation and put the economy on a firmer footing for the long haul. But getting shelter inflation under control will require action not just by the Fed, but also by federal, state, and local governments.

Because the bottom line is this: We need to build.

Perhaps the most effective reform to incentivize affordable home building would be to revisit zoning laws. In many communities across the country, zoning laws prohibit the construction of multifamily units. Seattle, for instance, is largely zoned for single-family homes. This has undeniably produced a city full of quiet, charming neighborhoods, and one can certainly understand some local resistance to loosening zoning. But it has certainly contributed to that city’s extraordinarily high home prices. Many towns in New Jersey are also zoned for single-family homes.

Other cities have rules that prevent existing homeowners from maximizing the space they already own. Some municipalities, for instance, ban homeowners from renting their garages, basements, or other excess spaces. Changes here would increase population density and lower housing costs by boosting supply with little-to-no construction needed.

Changes to the tax code could also spur more development. For instance, shifting from a property tax to a land value tax could encourage small, high-quality housing in a more compact footprint. These changes would also discourage landlords from letting their existing properties fall into disrepair or from leaving land vacant.

Some cities could also encourage the development of specific workforce housing near key employers. Areas dominated by tourism like the Jersey Shore are starved of housing for workers. Incentivizing workforce housing could begin to ease these supply shortages. And in those same tourist-heavy regions, local governments could look to limit the number of short-term rentals to ensure that local residents have places to live.

Given how long it takes to build new housing, most of these are not quick fixes; it will take years for supply to catch up with demand. So in the meantime, federal and state governments could look to increase housing subsidies for low-income Americans.

As a Federal Reserve Bank president, it is not my role to dictate congressional or local government policy. These are just ideas for consideration, and I remain neutral on the wisdom of any specific policy.

But I am not neutral on the need to deal with our shelter inflation problem. High housing inflation is a macroeconomic problem; money spent on housing is money not spent on education, durable goods, or meals out. And shelter inflation will eventually degrade the economic performance for the most costly areas as well. There is already evidence that the most expensive metro areas are not achieving their full economic potential because millions of would-be participants simply can’t afford to live there.

This is also, in my view, a moral issue. Simply put, in a country as wealthy as ours, Americans should be able to put a roof over their heads. Not to mention, if future Jersey boys like me with a fondness for hoagies want to do what I did and stay local, we need to make sure they can afford to do just that.

- The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.