Speakers who discussed the role of capital explored how to create successful collaborations that bring together public and private sector stakeholders and help attract new forms of capital for community and economic development purposes.

Connecting Communities to Capital Through Collaboration

Panelists in a session on connecting communities to capital through collaboration challenged participants to think about raising capital as important yet secondary to setting strategic and collaborative priorities. Tamar Kotelchuck, director of the Working Cities Challenge at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, discussed the cross-sector collaboration that is underway in New England. The Working Cities Challenge addresses the issue of limited resources in smaller cities by using a collective impact-type approach1 that is based on collaborative leadership in a community as a means to attract capital. Kotelchuck explained that the key goals of the Working Cities Challenge are to:

- Support bold, promising approaches that have the potential to transform the lives of low-income people and the communities in which they live

- Build resilient, cross-sector civic infrastructure that can tackle the complex challenges facing smaller industrial cities and achieve population-level results

- Move beyond programs and projects to focus on transforming systems and promoting integration across multiple systems and issues

- Drive private markets to work on behalf of low-income people by blending public, private, and philanthropic capital and deploying it in catalytic investments

- Collaborate with partners at the state and regional levels to broaden support for collaboration and leadership, focused on low- and moderate-income communities2

In the Working Cities Challenge, participating cities compete for three-year grant awards of $300,000 to $500,000 provided by local philanthropic partners. Kotelchuck explained, however, that this challenge is about more than funding: It is intended to create a learning community and use research and evaluation to encourage replication of successful strategies in other small cities.

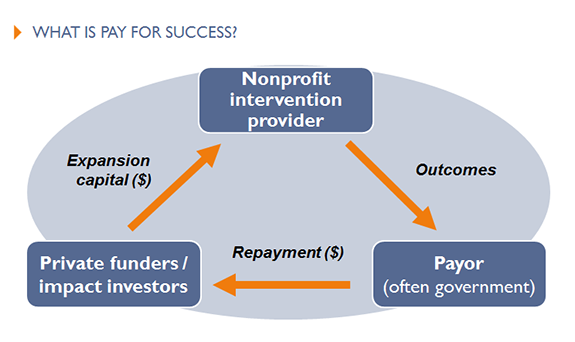

Jeff Shumway, vice president of advisory services at Social Finance, spoke about another way to use evaluation to encourage funding of effective strategies: social impact bonds and pay for success financing. Shumway discussed how these strategies have the potential to improve program delivery and rigor in performance measurement and increase accountability among service providers.3 He explained that, at its core, “pay for success is about measurably improving the lives of people most in need by driving government resources toward more effective programs.” Figure 1 illustrates how pay for success financing works.

Figure 1. From Jeff Shumway, “New Funding Tools for Government Challenges,” presented at Reinventing Our Communities, September 21, 2016; available here. Used with permission.

David Wood, director of the Initiative for Responsible Investment at the Hauser Institute for Civil Society in the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, explored how to strengthen community investment systems by bolstering their local capacity for capital absorption. He explained that many stakeholders find that attracting and deploying capital to advance a city’s priorities can often feel like a “heroic quest.” In order to simplify this difficult task, Wood, in partnership with Robin Hacke, senior fellow of the executive office of the Kresge Foundation, developed a framework to help cities improve their “capital absorption capacity”4 by focusing on three key functions of the community investment system. First, Wood said, a community should develop strategic priorities that encompass the collective vision of the community. Next, a pipeline of deals should be generated that will contribute to achieving that vision. Finally, an enabling environment will promote the execution of that pipeline.

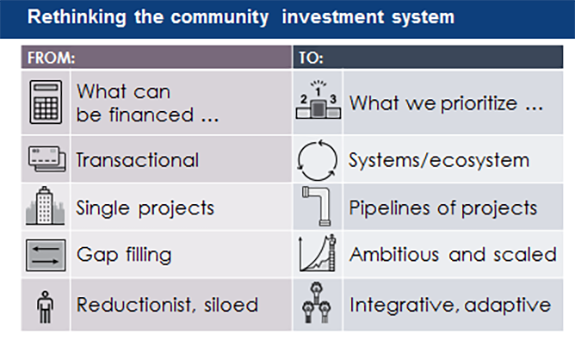

Wood encouraged participants to think about systems instead of transactions and about strategic priorities instead of financing opportunities. He said that common yet incorrect assumptions are that the key problem is a lack of capital and that a pipeline of investable deals is waiting to be funded if the capital is raised. Figure 2 shows how rethinking the community investment system can be accomplished.

Figure 2. From David Wood, “Strengthening Investment in Community Priorities: A Systems Approach,” presented at Reinventing Our Communities, September 21, 2016; available here. Used with permission.

New Funding Sources for Community and Economic Development

Panelists who presented in the session on new funding sources for community and economic development challenged participants to think about how to transform the current community investment system. Antony Bugg-Levine, chief executive officer at Nonprofit Finance Fund, discussed strategies that can effectively support the expansion of successful nonprofits. Unlike for-profit companies, nonprofits cannot run deficits funded by equity markets. Bugg-Levine said that there is a need for “nonprofit equity,” that is, investments toward creating high-performing nonprofit enterprises. These investments are needed so that nonprofits can expand operations, improve efficiency, and/or focus on strategic planning. This capital will allow organizations to build the capacity needed to deliver sustainable services.

Participants discussed the fact that philanthropic investments should strategically address the causes of social problems while charitable capital should be used to mitigate the symptoms. Bugg-Levine also stressed that government should assess the risk appetite of various types of investors and use its capital accordingly in order to strategically leverage additional capital toward solving social problems.

Bugg-Levine said that community development financial institutions (CDFIs) have proven that loans can be made successfully in low-income areas and be repaid. He challenged the audience to “not simply focus on moving more money, but rather, ask ourselves how can the money be used to transform communities and make our society more just.”

Bugg-Levine said that the CDFI industry is organized around meeting the needs of banks motivated by the Community Reinvestment Act. This can be somewhat problematic because these lenders tend to be risk-averse and are seeking to deploy short-term capital whereas the communities they serve are desperately in need of longer-term, patient capital. Panelists and participants agreed that the CDFI industry has not yet reached its potential due to some systemic and branding issues that prevent it from tapping into more traditional capital markets. By working with groups such as the Global Impact Investing Network,5 which Bugg-Levine founded, industry representatives are currently trying to tackle those pressing challenges.

Alya Kayal, director of policy and programs at US SIF: The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, explained that if those challenges are addressed, there is a large market of investors eager to channel their investment capital in a way that is consistent with their personal values. She discussed the demand for socially responsible investing (SRI), which considers environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) criteria in pursuit of long-term competitive financial returns and positive societal impact.

US SIF research found that, since 1995, there was a 14-fold increase in sustainable and responsible investing in the U.S., and that community investing specifically had grown from $4 billion to more than $121 billion in that same time period (Figure 3).6

Figure 3. From “2016 Report on US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends,” Washington, D.C.: US SIF Foundation, 2016; executive summary available here. Used with permission.

Kayal also discussed changes at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that allow small businesses to engage in crowdfunding, a popular tool to fund start-up projects and small businesses by pooling small monetary contributions from many individuals, typically through online platforms and social media. The use of crowdfunding expanded greatly in 2008 when credit was limited during the recession.

Crowdfunding platforms have continued to gain popularity, raising $16.2 billion in 2014, a 167 percent increase over the $6.1 billion raised in 2013.7 Ryan Feit, chief executive officer and cofounder of the online crowdfunding platform SeedInvest, spoke about the importance of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act.8 “This piece of legislation now allows small and medium-size businesses to turn customers into investors, therefore allowing communities to invest in themselves,” said Feit.

Figure 4. From Ryan Feit, “SeedInvest,” presented at Reinventing Our Communities, September 21, 2016; available here. Used with permission.

Feit shared that the long-term potential for crowdfunding far outweighs other financial technology (or fintech) market opportunities such as robo-advisors and online consumer and business lending platforms (Figure 4).

During the panel discussion, participants asked how they can educate our communities about these crowdfunding opportunities. Given the prevalence of smartphone ownership regardless of income level, panelists agreed that, although spreading awareness may be challenging, this capital innovation could bring opportunity to any community.

Conclusion

The Reinventing Our Communities conference fostered rich discussion regarding the role of capital in transforming our economies. Although opportunities exist to connect with new sources of funding for community and economic development, leaders in the field of community investing believe that collaboration and a cohesive community vision are essential to ensuring that capital is used in ways that effectively benefit the people and communities it is meant to serve.

Additional Resources

- David Wood, Katie Grace, and Robin Hacke, “The Capital Absorption Capacity of Places: A Research Agenda and Framework,” Initiative for Responsible Investment and Living Cities, Working Paper, March 2012; available at https://livingcities.s3.amazonaws.com/resource/ 137/download.pdf.

- “Capital and Collaboration: An In-Depth Look at the Community Investment System in Massachusetts Working Cities,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Initiative for Responsible Investment, and Kresge Foundation, August 2016; available at http://kresge.org/sites/default/ files/library/eo_1016_-_capital_collaboration_report_final.pdf.

- “Expanding the Market for Community Investment in the United States,” US SIF: The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, Initiative for Responsible Investment, and Milken Institute, July 2013; available at www.ussif.org/files/publications/ussif_expanding_markets.pdf.

- “Nonprofit Finance 101,” available at www.nonprofitfinancefund.org/ nonprofit-finance-101.

- Annie Dear, Alisa Helbitz, Rashmi Khare, et al., “Social Impact Bonds: The Early Years,” White paper, Social Finance, July 2016.

The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.

[1]Collective impact occurs when organizations from different sectors agree to solve a specific social problem by using a common agenda, aligning their efforts, and using common measures of success. More information on collective impact is available at https://www.fsg.org/publications/collective-impact.

[2]From Tamar Kotelchuck, “Working Cities Challenge,” presented at Reinventing Our Communities, September 21, 2016; available here.

[3]For more on pay for success financing, see Noelle St.Clair Baldini, “Pay for Success: Financing Research-Informed Practice,” Cascade 89, Fall 2015, available here.

[4]For more information on the concept of capital absorption capacity, see http://iri.hks.harvard.edu/capital-absorption.

[5]See https://thegiin.org.

[6]Data from “2016 Report on US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends,” Washington, D.C.: US SIF Foundation, 2016; executive summary available at http://ussifnewsite.membershipsoftware.org/files/SIF_Trends_16_Executive_Summary(1).pdf. The report describes community investment as providing low-income communities with access to credit, equity, capital, and basic banking products that they currently lack. This includes assets in community development banks, credit unions, loan funds, and community development venture capital.

[7]Erin Hobey, “Massolution Post Research Findings: Crowdfunding Market Grows 167% in 2014, Crowdfunding Platforms Raise $16.2 Billion,” Crowdfund Insider, March 31, 2015, available at www.crowdfundinsider.com/2015/03/65302-massolution-posts-research-findings-crowdfunding-market-grows-167-in-2014-crowdfunding-platforms-raise-16-2-billion.

[8]For more on the JOBS Act and crowdfunding, see Noelle St.Clair Baldini, “Capital for Communities: Regulatory Changes Support Impact Investing,” Cascade 93, Fall 2016, available here.